Mongolia's Gobi Bear: an Endangered Sub-Species

Only 30-50 Gobi bears may survive, but even this estimate is uncertain. They are known to persist only in the region of the Great Gobi Strictly Protected Area of southwestern Mongolia. Because of their present low population size, restricted range, and limited available habitat these bears are listed in the Mongolian Red Book of Endangered Species, a categorization that was validated by the bear’s designation as Critically Endangered in the November 2005 Mongolian Biodiversity Databank Assessment Workshop. Additionally, these bears must now accommodate large and far-reaching mineral extraction in their range.

As a part of the Gobi Bear Project, Craighead Beringia South has helped to initiate research and to develop science-based strategies that are effective for the recovery of Mongolia’s Gobi bear population from its present Critically Endangered status.

Gobi Bear research field crew, 25 July 2005, Gobi Desert.

Publications:

A population genetic comparison of argali sheep (Ovis ammon) in Mongolia using the ND5 gene of mitochondrial DNA; implications for conservation. (2004). Tserenbataa, T., Ramey, R. R., Ryder, O. A., Quinn, W., Reading, R. P. Molecular Ecology, 13, 1333-1339.

The gobi bear project, Conservation of the critically endangered Gobi Bear. (2008). Reynolds, H., Alaska, R., Amgalan, L., Tserenbataa, T., Craighead, D., Mijiddorj, B., Proctor, M., Ross, J., Tumendemberel, O., Nyambaya, G., Dovchindorj, G., Amgalan, B. 14.

Gobi Bear Population Survey 2009. (2009). Tumendemberel, O., Proctor, M., Reynolds, H., Luvsamjamba, A., Tserenbatataa, T., Batmunkh, M., Craighead, D., Yanjin, N., Paetkau, D.

Presence of the neurotoxic amino acids β -N-methylamino-L-alanine(BMAA) and 2,4-diamino-butyric acid (DAB) in shallow springs from the Gobi Desert. (2009). D. Craighead, J.S. Metcalf, S.A. Banack, L. Amgalan, H.V. Reynolds, and M. Batmunkh. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, 10: 1, 96 — 100.

Gobi Bear Population Survey 2009. O Tumendemberel, M Proctor, H Reynolds, L Amgalan. H., Luvsamjamba, A., Tserenbatataa, T., Batmunkh, M., Craighead, D., Yanjin, N., Paetkau, D. Gobi Bear Project Team.

Gobi bear population survey and conservation in Mongolia. (2010). Tumendemberel, O., Proctor, M., Reynolds, H., Luvsamjamba, A., Tserenbatataa, T., Batmunkh, M., Craighead, D., Yanjin, N., Paetkau, D. Gobi Bear Project Team.

My Place, Your Place, Our Place!: The Gobi Bear's Place in Mongolia. (2014). CBS/Gobi Bear Project.

Gobi Bear Abundance and Inter-Oases Movements, Gobi Desert, Mongolia. (2015). Tumendemberel, O., Proctor, M., Reynolds, H., Boulanger, J., Luvsamjamba, A., Tserenbataa, T., Batmunkh, M., Craighead, D., Yanjin, N., Paetkau, D. Urus, 26(2) 129-142.

MITOCHONDRIAL CYTOCHROME B GENE SEQUENCE DIVERSITY IN THE MONGOLIAN RED SQUIRREL, Sciurus vulgaris L. (2013). Odbayar Tumendemberel, Bayarlkhagva Damdin, Munkhjargal Bayarlkhagva, University of Wyoming.

Review of Gobi bear research (Ursus arctos gobiensis, Sokolov and Orlov, 1992). (2016). A Luvsamjamba, H Reynolds, A Yansanjav, T Tserenbataa, B Amgalan, et al. Arid Ecosystems, 6(3), 206-212.

Phylogeography, genetic diversity, and connectivity of brown bear populations in Central Asia. (2019). O Tumendemberel, A Zedrosser, MF Proctor, HV Reynolds, JR Adams, et al. PloS one, 14(8), e0220746.

Evolutionary history, demographics, and conservation of brown bears: filling the knowledge gap in Central Asia. (2020). Thesis for: Ph.D, Advisor: Andreas Zedrosser, Frank Rosell, Mona Sæbǿ, Michael Proctor, John Swenson, Lisette Waits, Project: Gobi bear ecological genetics and its phylogenetic studies.

Long‐term monitoring using DNA sampling reveals the dire demographic status of the critically endangered Gobi bear. (2021). O Tumendemberel, JM Tebbenkamp, A Zedrosser, MF Proctor, et al. Ecosphere, 12(8), e03696.

The gobi bear and the Mongolian Gobi Desert. CBS.

In November 2020, Odbayar Tumendemberel from USN’s PhD program in Ecology defended her thesis for the degree of PhD: Evolutionary history, demographics, and conservation of brown bears (Ursus arctos): filling the knowledge gap in Central Asia.

The aim of the PhD project was to answer two main questions 1) population demographics of critically endangered Gobi bears, 2) evolutionary history of brown bears in Central Asia. Between 1996-2018, we collected 2660 non-invasive genetic samples from brown bears in the Gobi Desert allowing us to identify and genetically monitor 65 unique individuals over 20 years. Based on mark-recapture analyses, annual population size was only 23-31 individuals. Additionally, Gobi bear population has a highly skewed sex ratio (3M:1F) and high degree of inbreeding. This suggests that Gobi bears are one of the most critically endangered population in the world. For the evolutionary questions, we collected genetic samples from 119 brown bears across 8 poorly studied geographic locations in Central Asia and used traditional markers (i.e. mitochondrial DNA and nDNA microsatellites) and whole genome data. We also included Genbank data from brown bears in Europe and North America to understand the wide-range evolutionary history.

We found 6-8 divergent brown bear lineages in Northern Asia, Europe (2 potential subclades), Gobi, Himalaya, Ancestral lineage in North Asia, North America (2 potential subclades). These results suggest that bears in Himalaya and Gobi are different evolutionary significant units and 2 subspecies including Ursus arctos gobiensis and Ursus arctos isabellinus. These demographics and genetic results highlight the critical status and uniqueness of Gobi bears and answered fundamental question necessary for effective conservation.

(University of South-Eastern Norway, 2020)

In 2011, Derek Craighead exhibited the following images taken during eight years while working alongside his Mongolian friends and colleagues. Fewer than 45 Gobi bears exist. This venerable lineage of the brown or grizzly bear face and implausible future. The Gobi bear team is in a race against time to find a path to recovery for this critically endangered bear of the desert.

Entrance to the Gobi Bear Strictly Protected Area. Photographs and text by Derek Craighead.

To get from “here to there“ (in the Gobi Desert ) is usually an arduous journey of trial and error made precarious by the shortage of fuel and water.

The Gobi Bear Research Team's first season in the field.

Genghis Khan (Genghis Khan): The Gobi bear wandered the vast central Asian steppe for 40,000 years, content in its position as the dominant species. But less than 1000 years ago under the influence of Genghis Khan nomadic family herders call coalesced into Mongal clans and then unified as the World's largest and most influential Empire. Genghis Khan was an early advocate for wildlife management. Since then, the Gobe bear’s habitat has dwindled and now only a few bears persist.

A roadside frontier town along one of the meandering dirt roads leading to the Gobi Desert.

The perfect nomadic home.

The world over, an outhouse looks familiar.

Camped in an Aeolian deflation zone. The sustained Gobi winds have removed the fine particles of rock and sand leaving a surface pavement of varnished black rock fragments. The rock mantle protects the underlying dirt from wind erosion. Manganese, hydroxides, and clay minerals form the varnish and provide the shine.

The Gobi bear research team en route from Ulaanbaatar to their research camp in the Gobi Desert.

An early spring shower has beguiled this iris out of the rock pan soil.

Mongolian cowboy lassoes a colt with an Uurga, a rope loop at the end of a long pole.

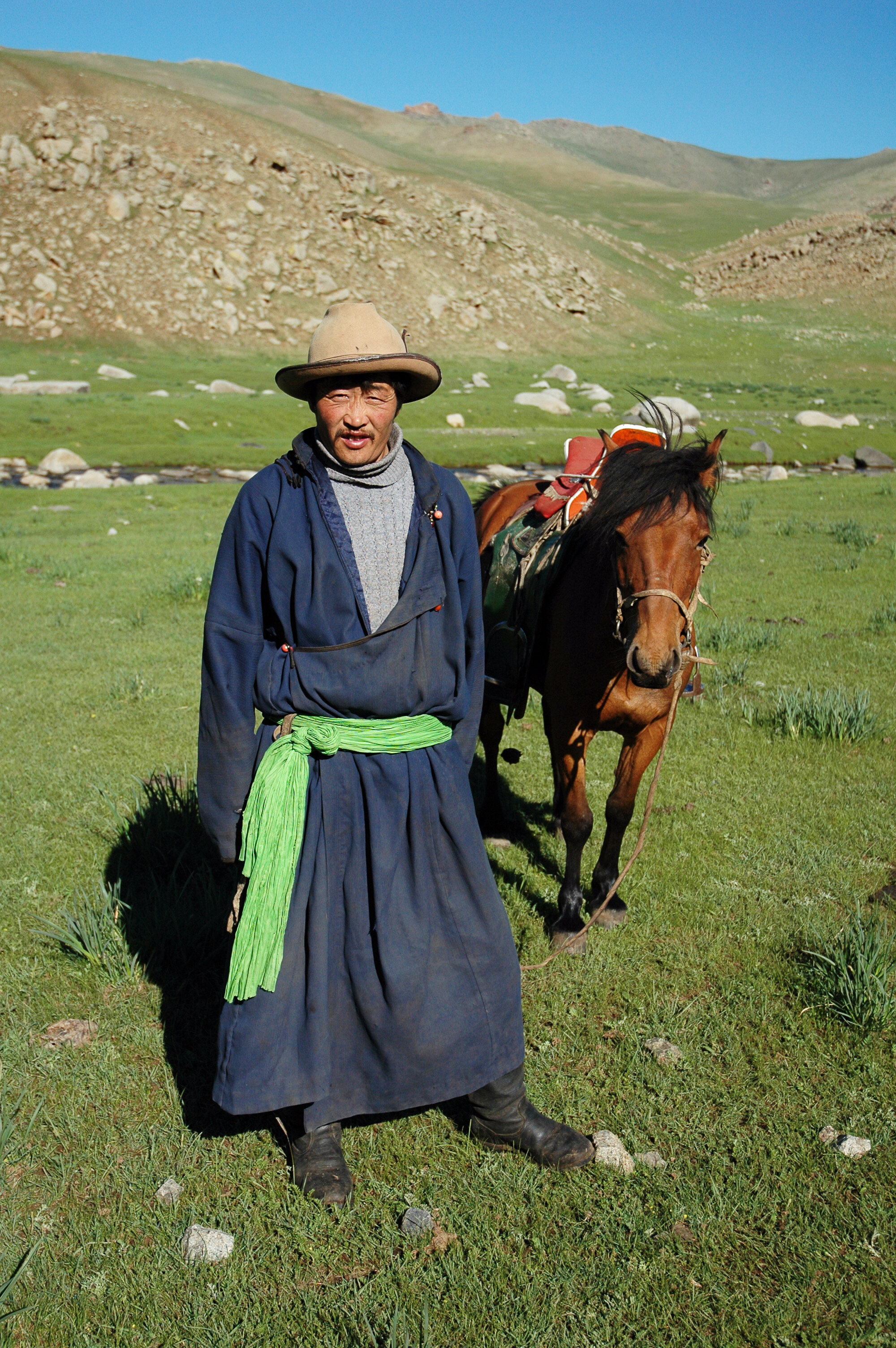

Dressed for a day on horseback tending the goat herd.

"Yurt" is the West's misnomer for ger, the traditional Mongolian dwelling made of heavy felt wrapped around a wooden lattice and rafter poles. Like the North American Indian tipi, it is a comfortable, all season, home and facilely portable.

With anticipation, the crew awaits a well deserved meal of noodles and dried camel.

Sheep-head soup, a desert delicacy.

At Sharholtz, a stone get provides warmth and comfort to the crew

Ladling precious drinking water from deep under a rock outcropping.

These claws, although half the length of a North American Brown bear are exceptionally long for a Gobi bear who survives by digging rhubarb roots out of the abrasive volcanic soil of the Gobi Desert.

The normally long claws are worn to numbs by the abrasive volcanic soil.

The Gobi desert is a landscape of volcanic rock and occasional sandstone intrusions, both extremely abrasive. The teeth of this middle aged bear are worn to the gums, a result of chewing the dirt covered roots of the rhubarb plant.

Rhubarb Root: The below portion of the rhubarb plant provides the majority of the Gobi bear’s food. It is high in protein and carbohydrates and large enough to make it energetically profitable to excavate. The upper portion of the rhubarb plant appears only after sufficient rainfall; showers are short-lived and sporadic in the desert.

Team members dissect bear scat, identifying undigested food parts and collecting a DNA sample.

ear Poop: Although it appears as if these ephedrine berries have passed through undigested, they provide some nutrition, but are also laced with a toxic alkaloid.

Ephedra: Ephedraceae species are found worldwide. This species E. sinica is native to Asia and contains the alkaloids ephedrine and pseudoephedrine that are a stimulant that constricts blood vessels and increases blood pressure and heart rate.

A sow and her offspring search for food in the Gobi desert, this healthy family represents a glimmer of hope.

A lone Gobi bear picks its way along a rocky desert ridge.

Meeting of the Minds: Even though there was often no common language between the Mongolian and American team researchers, work preceded smoothly and enjoyably for weeks on end.

"Looking for a needle in a haystack." Landscape of the Gobi bear.

The oblique evantide view across an alluvial plain highlights the shachal shrubs, and ecological equivalent of Wyoming’s sage brush steppe.

Trails diverging from an oasis. The travelers are wild ass, wild camel, gazelles and Gobi bear.

This tenacious bear is an iconic symbol of the Mongolian people.

A ranger listens intently for the radio signal of a Gobi bear.

The contented face on one of Mongolia's estimated 50,000 domestic camels. The wild Bactarian Camel was domesticated over 4,000 years ago and because they are tolerant of cold, drought and high altitudes, continue to be utilized throughout inner Asia.

The wooden nose piercings serve the same function as a bull ring to help control the animal. In an uncertain world, the Bactarian, or two humped camel, stores emergency fat in its' humps to survive.

The wild camel is smaller, lissome, and has more conical shaped humps compared to the domesticated form. The wild camel is classified as a critically endangered species in Mongolia, its' range is sympatric with the Gobi bear and faces the same threat of extinction from habitat loss, persecution, and conflicts from human commerce.

The Gobi bear inhabits a landscape bound by inhospitable terrain. At 45 degrees latitude and 7000 feet elevation it is a land of extremes. Temperatures range from -40 F to 122 F, and annual rainfall average 7.6 inches per year. The bear is prevented from regaining its' ancestral land to the north, an expansive, fertile, sea of grass, the Asian steppe, because what once was suitable bear habitat is now over-grazed by 42.2 million head of goats, sheep, horses, and cattle (2008). To expand south is to find themselves in the endless desolation of the fifth largest desert in the world. The Great Gobi Strictly Protected Area maintains supplemental feed for the bear.

Derek Craighead grew up near Moose, Wyoming and raised his family there. He is President of Craighead Beringia South, a nonprofit wildlife research and education institute in Kelly, WY. He was recognized by the Mongolian Government in 2009 with the Parliamentary title of Honorable Ecologist for his service to their country. This commendation had never before been awarded to a non-Mongolian.

For sixteen years, Derek Craighead and the Gobi Bear Team of researchers have been working to recover the population (<45) of the critically endangered Gobi Bear in the Gobi Desert of southern Mongolia.